Rich Health Harvest in Native Fruit

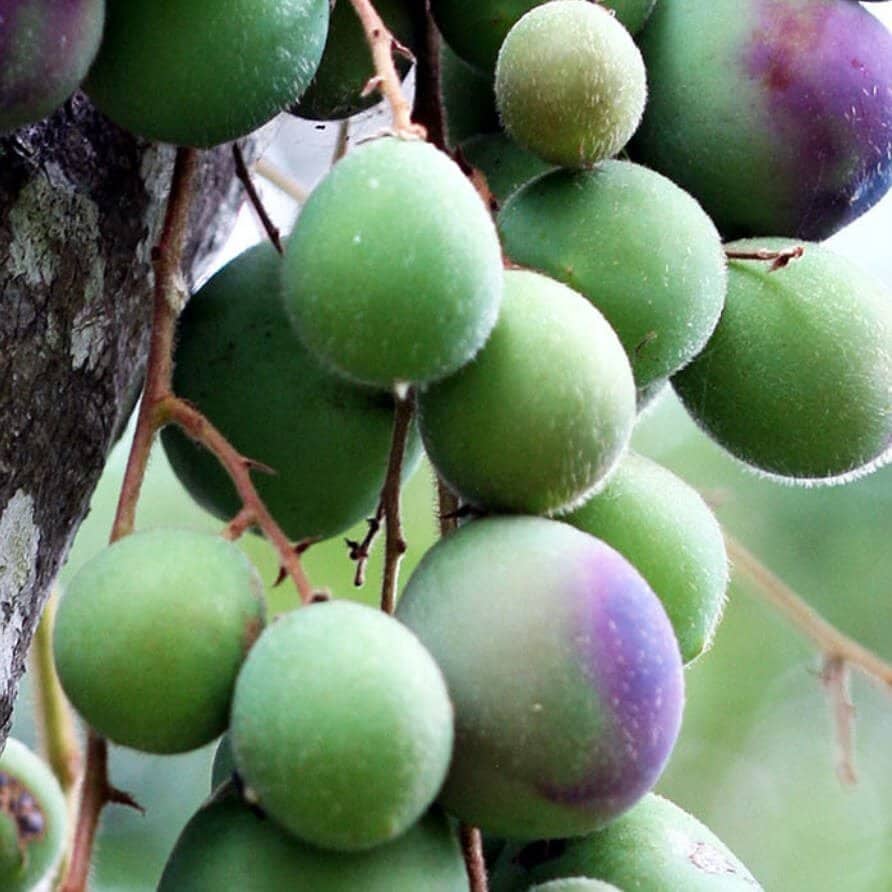

06/07/2015Kakadu plums have more vitamin C than any other natural food found on the planet – or 50 times that of an orange – and it looks as though people are starting to pay attention.

Only a few years ago, the bush fruit was left to fall from the trees and rot on the ground in Australia’s far north, due to a lack of interest, but government-sponsored research into the health benefits of the plum is tying in neatly with a consumer trend towards “super fruits”: fruits with bigger than normal concentrations of vitamins.

So move over China with your pomelos and gojis and Brazil with your guarana beans and acai berries; Kakadu plums need some shelf space.

Melbourne dietitian Hayley Blieden is among those trying to sell Australia on the health benefits of locally grown bush foods, through her company The Australian Superfood Co’s health bars, powders and air- dried fruits. “Why, when superfoods were the main [food] trend, was nothing coming out of Australia?” she asks. “Everything was being imported.”

This is a new enterprise, launched only three months ago, and Blieden says she is trying to source as much raw material as she can through Indigenous enterprises.

“I was quite surprised how many of the native fruits have little connection with Aboriginal communities anymore,” she says. Her products include Kakadu plums, Davidson plums, finger limes, quandongs, riberries, lemon myrtle and wattleseed.

So far, the only ingredient she has been able to source through Aboriginal communities is the Kakadu plum, from the Wadeye community, 417 kilometres south- west of Darwin. “We would love to purchase more ingredients from Indigenous communities but we haven’t had any luck finding supply,” she says.

The Wadeye harvest is organised through the local women’s centre and only Indigenous people are allowed to pick and process the fruit (on the condition that their children, if school age, are at school).

“They can never be cut out of the equation,” Blieden says. “The Aboriginal people own the rights to the fruits. They go out, often on weekends, they pick the fruit, they take the whole family out, it is a really fun time. The women are climbing trees, they are singing and dancing and having fun with family and friends. They bring [the fruit] back during the week and sell it to the women’s centre.”

This has given work to about 200 women for three to six months of the year, providing a major boost for the community of 2500, and where the unemployment rate is said to be about 84 per cent (not including people who hunt or produce art to boost their livelihoods). Wadeye is the largest Indigenous community in the Northern Territory and its sixth-most populous town.

Blieden says she takes a fifth of the harvest, but aims to take a bigger share. She is competing with the makers of beauty products, which use the plum as an ingredient and also seafood manufacturers, which have found it is a good natural preservative for prawns. “There is a huge global demand for the Kakadu plums and that started in the last two years only. Now, I think, they are struggling to meet demand.

“A big part of the business in the future will be about helping Indigenous communities to cultivate these fruits.”

She says “a few” hundreds of thousands of dollars have been contributed to get her business up and running, with the help of some investment from a family friend. She has also benefited from the advice of her father and business partner, Ralph Wollner, a well-known business coach and consultant and a former chief executive of businesses in manufacturing, IT and logistics.

Blieden became interested in nutrition when she left school because of her interest in sports and after observing the food issues of her schoolmates.

“I had some friends with eating disorders, a few friends who were quite overweight and always struggling with their diet and also being in sport and seeing how it can affect your performance. I wanted to learn more and educate and try to help people – not only from a nutritional point of view of eating the right foods, but also from the mental health side of things so they didn’t have to battle with these demons daily.”

Her work, until 2011, as a dietitian for the North Melbourne Football Club brought her into contact with some Indigenous players and she observed how their physical condition would change after they returned from a break at home, depending on their diet and lifestyle (some for the better, and some for the worse, depending on what they were consuming while they were away).

At the same time, she was motivated by Close The Gap, a campaign which aims to improve the health and life expectancy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people within a generation to the levels enjoyed by non-Indigenous Australians. “I just couldn’t understand how, in a country like Australia, there could be such a health disparity and people couldn’t have access to fresh fruit and vegetables on a daily basis,” she says.

Blieden studied for an MBA and spent four years researching bush foods with the idea of starting a business. “The nutrition dietetics had given me a lot of knowledge… and I wanted to produce products in a marketplace where there are so many processed foods and so much misinformation,” she says. “The food industry, as a whole, is trying to confuse and trick consumers with clever marketing. I wanted to be able to create a brand that consumers could trust and benefit from.”

Blieden hired a food technologist to try to create a snack bar, but initial results were disappointing. “What came back literally tasted like cardboard. It evolved from there.”

This article was written by Fiona Smith and appeared in the Australian Financial Review 4 July 2015.